…news can erupt really fast. Anyone can make the news. Anyone can break the news.

…news can erupt really fast. Anyone can make the news. Anyone can break the news.

The Davies Method consists of candid, clear communication aimed at achieving calm through empathetically addressing issues and consistently communicating progress towards resolution.

Takeaways and Teachable Moments

KNOW WHAT CRISES YOU ARE LIKELY TO FACE AND CREATE A PLAN FOR RESPONDING.

RESPOND QUICKLY AND PROVIDE FREQUENT UPDATES.

UNDERSTAND THAT TODAY’S NEWS CYCLE IS FAST, EMOTIONALLY DRIVEN AND IMAGE-FOCUSED.

Feature List Item 4

This is where the text for your Feature List Item should go. It's best to keep it short and sweet.

ADDRESS FEAR AND ANXIETY, RATHER THAN GLOSSING OVER THEM.

WORK TO ACHIEVE AND COMMUNICATE CALM AMIDST THE CHAOS.

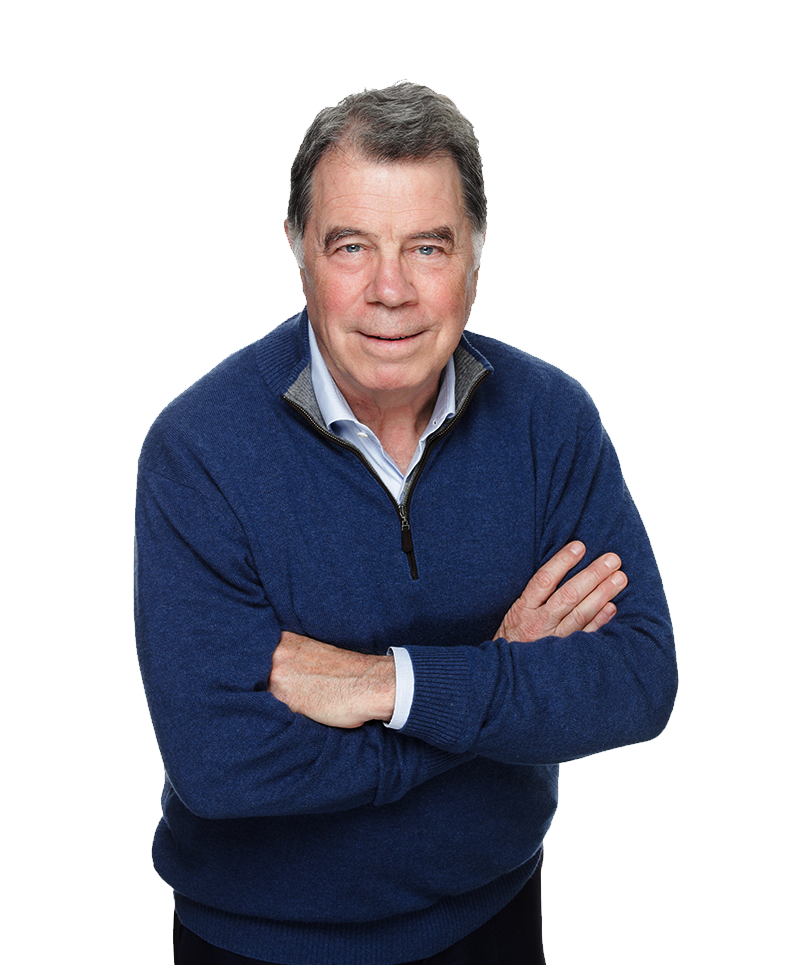

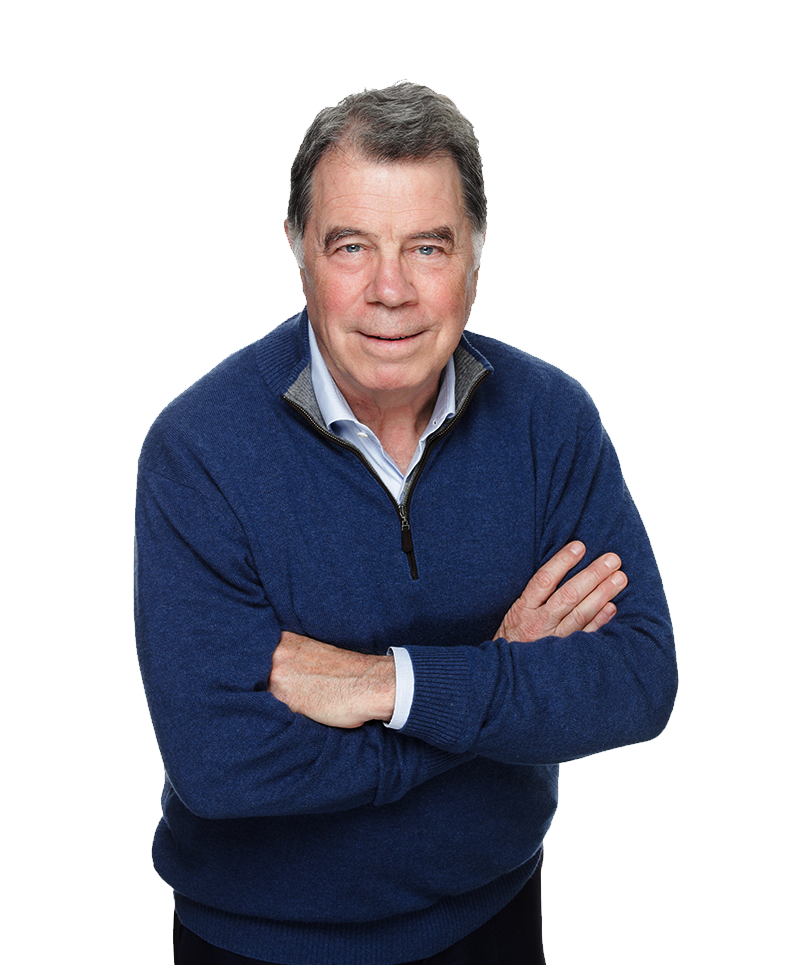

Begin here and follow along as John Davies discusses how everything has changed in today's fast-paced world where everyone has a media voice. And at the same time, nothing has changed. People still need constant clear and calm communication during a crisis. This episode outlines the application of John's time-proven method within the parameters of today's rapidly changing environment.

John has spent years managing crisis, both internal and external. His skill at guiding people and organizations through crisis situations has been developed through countless real-world scenarios. Every step in the Davies Method has been proven effective. The second episode of this series will reveal why John's clients immediately reach for his number when a potential crisis arises.

Crisis Happens: Everything Has Changed Nothing Has Changed

Mark: Welcome to the second episode of Crisis Communications with John Davies. I’m Mark Sylvester, now let’s get started and talk with John.

John, I want to talk about how everything has changed and nothing has changed. I mean, we've been ... I'm thinking about how long companies have been dealing with crisis and what a crisis is, so why don't we just reframe what a crisis is?

John: Well, if you look at ... It's all part of the world of communicating, communications, all of the subsets and all of the issues, so crisis is communicating when it's really hard or impossible to communicate.

Mark: Oh, got it.

John: It's hard because you've got to tell some hard truths, and you have to tell the truth. Sometimes, it's impossible because no one wants to listen to you. We'll talk about that in our session on what's the difference between hazard and outrage, because there's some points where you just want to say, "You yell at us. We want to just hear you yell at us. Tell us everything that's wrong." It's a hard communications tool, and it's a moment where you don't get to have long-time things. You don't have to talk a lot. You’ve got to be on point, and you got to be out there.

It's a difficult communications time, but it also is a time where you can come out of a crisis with a stronger brand. You can come out of a crisis with people who really care about you. The classic crisis case study is Johnson & Johnson with Tylenol where the CEO and the team at Johnson & Johnson just did it perfect. They created the benchmark. By the way, I've met at programs and seminars and conferences, I've met the guy who is the genius of it who like 150 times I think...

Mark: Really?

John: Yeah, it's 150 different people that where the change is. You sit at a conference and, "I was the one that came up with this."

Mark: Oh, got it. Got it.

John: I mean, it's one of those that it was so successful, everyone in the world took credit for it, but it was really well done. The annual report that year continued. They had Johnson & Johnson logo on the cover, the beautiful red, and they had the corner turned on the top of the page like a ...

Mark: Like a peel-back, yeah.

John: A peel-back, and it said "An Eventful Year."

Mark: Oh, nice.

John: They sort of taught us all how to do it, which is hard.

Mark: You talk about knowing, right, this understanding, so talk a bit more about that.

John: You can't go into communicating on something unless you know what you're facing, right?

Mark: Sure.

John: You got to know what you face so, when you're doing the plan, know what you're going to face. What could you face? We have a worksheet and a little brainstorm session that we can put up here, and you can go through it and figure out what you could possibly ...

Mark: Oh, got it.

John: When we do in-house training for crisis and planning, it's like everyone needs to figure out, "What could we face?"

Mark: You know what I call that? I call that a premortem.

John: A premortem. You're just like ...

Mark: You just think about what are all the things ..

John: No, I love ... Yeah, that's really good.

Mark: That's the right word, right?

John: Right, in a lot of ways it is. We have two or three questions and get it out. Then, what can we face? How could we respond?

Mark: So, what are all the potential answers to that thing?

John: What could we do, what would it be and, again, we're highlighting a lot of things that we'll do in more checklists, but I want to have written press releases.

Mark: Already done.

John: How would we respond without the data in there. You know why? I get everyone to approve the language. I get everyone to approve all the little stuff.

Mark: Which usually takes a long time, and in a situation where you have no time, which we've established.

John: Then, we want to know, who do we need to talk to?

Mark: Yeah, but what do they call it, a call chain, like here are all the people were going to call?

John: Interesting that you say call. You're dating yourself.

Mark: Oh, I'm sorry. Who are we going to text?

John: Who are we going to text, who are we going to email, but the most important thing is what you just said, who do we need to call?

Mark: Right.

John: Because those are the people we always forget, so who are the stakeholders? Who are the people that must know, who must hear from someone? They get left out.

Mark: This is part of the planning.

John: That's all part of the plan, so you’ve got to have that list, and who's going to call them? Oh, well, the VP of whatever is on vacation, so what's our backup? Who's second? If there's not a third, then it goes up the ladder, not down the ladder, right?

Mark: Just hit me. How often should ... I could see that this is probably half a day to a day with the right people sitting down and making this plan. I love the idea of writing a press release. That's brilliant, right?

John: You're right.

Mark: That's brilliant because now, that's all done. How often do we check back on that?

John: Once a year, for sure.

Mark: Just once a year, okay.

John: Once a year should be good.

Mark: Put it on somebody's checklist.

John: Well, and then you should drill it again so, with the potential environmental type dangers or crisis, we drill them, and many industries that are regulated are required to do drills, and the federal government and state governments do the drill with you.

Mark: No kidding?

John: One of the things we do for clients, we do the drill with them with the state and federal governments, and they get rave reviews for the team. What I do is, I bring in for probably three or four of those, I'll bring in junior team members who do a shadow program, and it's so fun because they get to do three or four of them as watching from the back and do it on their own.

Mark: It feels like a mock trial.

John: It's just like a mock trial. My favorite thing that ever happened, we're leading a huge national one. It's somewhere in the Southeast. The federal agency's there, a bunch of state agencies, Coast Guard, everyone's there, and my person leading the entire crisis communications walks by, and everyone wears an apron at this one. This says who you are. It is really fun because ... The deal is, there's a danger to an apron, right?

Mark: What's the danger?

John: You got cords, and you got pockets, so she walks by the coffee thing.

Mark: Oh, no!

John: It gets caught on her cord, and she knocks over three big kettles of coffee. It creates a real crisis for the day, but that big of a drill with that many people, sometimes three days.

Mark: No kidding! Again, we're going to get into risks and all of that.

John: So, what could you face? What are the things we could face? You don't always get them all, and then how can you respond? By the way, how could we prevent them? How could we prevent?

Mark: The premortem.

John: Exactly, so who do we need to? Who are the stakeholders, up and down the list, every potential stakeholder. Who's best to talk to them? How are we going to talk to them? How are we going to get messages out? We've got to talk to the ...

Mark: I want us then, with this show, we're going to talk about that.

John: We're going to talk about one way of getting them out, and then how do we craft the message? Even though we have a format, we have an approved format, how are we going to craft a message? Who's involved? I dealt with a day-long ridiculous crisis created by a political figure who was sending out press releases to the national media about an offshore platform that there was a sheen around it, and someone saw it on a boat and called him, and he was making it into a big deal. You can't say anything until we know what the sheen is. We're like, nothing leaked.

Mark: Right.

John: I mean, no gauge, no nothing, no leak, no nothing. My client doesn't want to say anything, doesn't want to say anything, one of the top four oil companies in the world? About 4 o'clock in the afternoon, they go, "Okay, this is really bad. We are having one of our senior officials come to the platform," and they washed off the deck, and it was soap. The soap they use on the platforms are biodegradable.

Mark: I've seen that.

John: Biodegradable, and that's all it was. It was a biodegradable soap that was just floating there.

Mark: So, that gets back to just understanding the situation.

John: Yeah. I don't think any of us would've put on the list, we could have a biodegradable silt floating on a sheen, and some politician, looking to get their name in the Wall Street Journal, goes after it. Still, how do you craft a message on that?

Mark: So now, that's a great transition because now, how do we apply these principles in the digital age where everything's changed? We talk about Twitter gets out there instantly, Facebook. People on an incident now, there's going to be a, depending on how many people are there, a dozen cameras are going to be out, and all of this just floods the airway. You talk about anybody can break news. How is, the title of the show, "Everything is changed, and nothing is changed."

John: Everything is changed, and I actually think the digital/social has made my job easier.

Mark: How's that?

John: Because my number one principle and the number one failure of most crisis communications is, you don't get out a response earlier. The classic, so when we have a team shadowing when we have a crisis, I have them sending me reports like I'm the media and I'm the client. I'm watching what they're doing.

Their first report comes out about three hours after our first real report came up in the drill. The question is, "So, when are you going to get me something? When are we going to get a release out? When are we going to write the statement for the press conference?" You know what the answer is? We need to know more. "Well, when are you going to know everything you need to know?" You know what the answer to that is? In about a month. You never know enough the day of a crisis. You still have to talk to people, so having social and digital media helps you with the urgency of that media pushing. You’ve got to get out there with something.

Mark: Right.

John: You're talking about Twitter. Twitter's greatest ... If you look at the number of people that are on Twitter, who's on Twitter, more than ...

Mark: The media.

John: The media, and how many media ...

Mark: Number one.

John: Number one, so it's a great way to talk to the media.

Mark: Exactly.

John: It's a great tool, and the other is, you know, you don't have a lot of characters. I mean, we used to have 140. Now, we ...

Mark: right.

John: You can't go over and explain so, as a communicator, I love it. Everything that's changed is the immediacy in what's happening, but nothing's changed because the deal is, in the digital age, social media age, it can erupt at any time. Well, it's always erupted at any time.

Mark: We started off the show by saying I love that idea of having press releases already ready.

John: Right.

Mark: Would you ...

John: Yes.

Mark: Should we chamber up a bunch of tweets?

John: Yeah, of course. Same thing, sorry. The same exact thing. But here's the deal, a tweet is the crafted message without the boiler plate.

Mark: Yes.

John: Right?

Mark: Yes.

John: So, you know what you're going to do, you know how you can do it, and the deal is, think about getting a tweet approved through a big corporate structure.

Mark: That's probably challenging.

John: Yeah, and it's got to go fast, and it's going to go to everyone.

Mark: Everybody knows that.

John: Yes, and that's the deal, so the deal ... In this era of social, it can erupt really fast at any time. It can erupt in a way out of nowhere, and then anyone can make the news. Anyone can break the news. So, in the past, a reporter that's on the air or writing a paper or on the radio, But right now...

Mark: Who's the journalist?

John: You got it.

Mark: So, there's a blurring, isn't there, between mainstream media and ...

John: The boundary has been totally blurred. However, as we've gone into this era of who's controlling the media, we all have a little more doubt about what comes up on digital and social media now. We look at it, say, "Hmm. Hmm. Is that true? I wonder if that's true," so we look for a credible source.

Mark: We talked about credibility earlier.

John: I think there's a credibility media so, as you look at five years ago, things break into social media, anyone could break it, everyone believed it. Now, people are looking for a real source and, depending on your political ideology, there's some sources that you don't believe.

Mark: Right, and it feels like partisan issues shouldn't be involved in crisis. But sorry, that's the air we breathe now.

John: The other challenge is, everyone's competing for breaking news. You know, more panic in an hour.

Mark: Who has more panic this hour?

John: Right, exactly. The other thing that has changed and hasn't changed, again, there's more of an urgency, more of a panic to it, is the public is more aversive to fear and danger now than they've ever been.

Mark: Well, it feels like it's all around us.

John: Yeah, well, I wonder why? Why do you think it feels that way?

Mark: Because, well, tell me. I thought this was my show. I get to ask you the questions.

John: It's to keep us ... There's a lot of reasons, but the two main ones, some people love that we're all in a state of fear because then they can mess with us in their issues, and they can make us be worried about everything, and then they can manipulate, and the media needs to get our eyeballs. Our eyeballs are leaving the media. We're getting our news from so many places. We can read a deep article. We can get deeper and deeper, so the media, to keep us watching, to keep us watching a show, has to make us have a little panic.

Mark: So then, we have a bit of a conflict here ...

John: We do.

Mark: ... because you have a crisis. There's an actual crisis, then we have the manufactured crisis, or the frenetic energy around that.

John: The stock market's down, the most its been down today!

Mark: Exactly.

John: Stay tuned!

Mark: Exactly, and yet you've said that crisis is communications in a state of chaos, and what we want to do is be calm, so we have a natural conflict between the chaos and the goal of the crisis communicator, which is to achieve calm.

John: It is. There's so many good things for dealing a crisis today, as well as difficult things. Because there's so much alarm, so much panic that people don't freak out as quickly because there's so much else. We're living at this panic stage anyway.

Mark: This is only a panic of four, so we're good.

John: Right. The news cycle turns fast, too.

Mark: Two hours, I think.

John: Oh, my gosh!

Mark: ... is my guess.

John: The news cycle, a big crisis with something really bad, you're going to have a day where they're going to be covering and covering, covering unless there's three more news stories, and then the next day, it settles. In the old days, I mean, even just the BP spill in the gulf that someone happened to put a camera down there that we could watch the camera as the oil spewed out, which is crazy, but that went on for ten, fifteen days as a top news item. How would you like to play with that? That was a nightmare.

The news cycle changes so much faster right now, so you’ve got to play that, which means you got to get out there faster, you’ve got to give them the news of what's going on and move. With the boundaries just melted, that makes it hard, but the public is so risk-averse and fear-driven that they live on the edge and one more thing can put them off. They make immediate decision, "I hate Company X now. I don't trust Company X."

Mark: Yeah, they're done, they're done.

John: Then, you have advocacy groups, and that's a really nice way of saying it, so advocacy groups, meaning people have a point.

Mark: What's the nice way of saying it?

John: Well, that's a nice way of saying it. The not nice way is people who have a vested interest in your demise.

Mark: Your demise.

John: There's two groups in that. One is your competitors. We all know what that means, but advocacy group because they want to raise money off it, and they want it to be a panic, and they want to make ... There are groups that raise billions of dollars.

Mark: I've heard of that… where this really bad thing happened to someone, and they turn that into a fundraising letter, and I'm like, how did you do that?

John: I mean, it's bad. It's really bad. I have clients that are the subject of, not crisis happening, but things that they're planning on doing that there are groups that have raised tens of millions of dollars a year by writing about it. I always tell them, "What happens after this goes away? You're going to lose all this money." The other thing that has changed is, it's become more emotional. It's more emotionally driven. When you think about the old days, the news would be ...

Mark: Old days. You mean last week?

John: No, no, I mean like 15, 20 years ago. If there was something really a crisis in the news, you'd hear, "Beep-beep-beep-beep! Beep-beep-beep-beep! We have breaking news!" It's every hour now, so it's much more emotionally driven, so they have to drive the emotion up because when we used to hear that, for many people over time, it's something ...

Mark: Red text, red screen.

John: You got it, and it's like ... Right. It's really image-focused now, very imaged.

Mark: At the end of the day, I'll hear what happened. Was there any news today? Yeah, it was just breaking news all day.

John: It was. And by the way, I was with a gentleman when the fire broke out on an airplane. We were waiting to take a flight back to Santa Barbara where you and I happen to live, and that person was following ... I'm following on a couple of news sources and getting texts from a fire chief in another town telling me what's happening, and my friend who was on the plane, as we were getting on and getting off, was picking it off from Twitter. It was like 10, 15 years ago before Twitter was a news feed. That was you. I don't know if you remember it. We were on a flight together. It was you.

Mark: Oh, that's right!

John: It was crazy, and then we flew into town, and they circled by where the fire was.

Mark: We saw it.

John: We saw it, and we were like, "Oh, man! This is a lot worse than anyone said." It was a big fire.

Mark: When you said image-focused, what does that mean?

John: That's what I'm talking about. Think about our ability to get images out now.

Mark: Oh, got it!

John: Right?

Mark: It's that visual impact when I see that thing, oh, my. We're going to talk about outrage in another show.

John: The deal is, when you see it, it's like, "Oh, oh, that's truth. That's truth," and what you and I saw, that's what I was going to on this. You were reading 140 characters back then. I'm getting texts and emails from my friends in the fire department telling me, "No, it's under control. They know where it's going." Usually, these guys are like, "If we have a little wind pickup, we could have a real problem to the east or the west or whatever," but when we flew over it, I mean, my eyes popped out of my head. When I drew home and I drove up a couple of streets to get closer and I see it's like lipping at the hill, but it wasn't, but the idea ... Image focus tells you more.

Mark: That's part of the everything that's changed because it's gotten so easy for us to either stream live or do whatever. When we think about ... We've been talking about the role of fear and anxiety and controlling this, I'm just curious. How do you address that with your messaging?

John: That's the key is you got to address it, number one. If I tell you when you're in a state of panic or you live in a state of fear, "Don't worry," I lose you.

Mark: What do you tell me instead of, "Don't worry," because I buy that.

John: You tell them transparently what happened. We have had an incident. We have had an issue. We had a blank today, and this is what happened. We don't know the exact cause. We now have it under control. In other words, you're not getting into a bunch of BS. Okay, so I'm thinking of just insert the name of any disaster movie here where the powers that be say, "There's a dirty bomb." Let's just think of one of these ... Now, we're going to bring Jack Bower in.

Mark: Right, and we say, "We can't tell everybody because there'll be a panic."

John: Right. Well, that's a different issue, right? You want to be the person that makes that decision?

Mark: I mean, that's what I'm ...

John: No, it's the whole point.

Mark: Because, if I'm afraid something bad has happened, and I'm afraid.

John: What do you think the judgment is, what they do every time, right, on Jack Bower? I can give you "If we don't stop this, thousands, hundreds of thousands, millions of people are going to die. We need to tell them." Well, if we tell them, hundreds and millions of people are going to die anyway because they're not going to be able to get out of the city, and they're going to be trampling one another and killing one another, right? So, basically, it doesn't do any good to tell them, and it could do worse.

Mark: Right, so in this case, tackling fear is ...

John: You’ve got to take it head on. You can't say, "This isn't a problem", but you can say, "It is now under control" or, "It's been contained."

Mark: Right.

John: "It's in this area."

Mark: And that will calm because, again, it's this voice of calm.

John: You got it. The deal is, the whole idea with fear today, and do we want to get into that now? Is that a good idea?

Mark: I want to finish with that because I think that's an important bit because I know there's some science behind this.

John: There's a lot of science behind it now, and so we have a lack of attention to things these days because so much is happening but, also, fear drives the tension up, so I believe there are three things that you have to play with fear. One is that there are people who like it that we are all in a state of fear.

Mark: Okay.

John: This isn't the subject of the show to go into.

Mark: Number two?

John: Number two is, it's how our brain functions.

Mark: Yep.

John: I mean, I want to get into details with it, and this a little difficult because it's really a very visual thing, but our brain functions with fear. Those of us ...

Mark: Fight or flight, right?

John: And there's a third one, freeze.

Mark: Right. We've talked about that.

John: People don't talk about freeze. I don't know why people forget freeze. Then, the last is, it's how the media keeps us watching, as I talked about before, so the media keeps us watching by doing it.

Mark: That's how we keep people listening to the show, John, because we have so much more to go.

John: So let's stop and pick this up in the next show?

Mark: I'm thinking we ...

John: Next week.

Mark: I think we wanted to ...

John: Do you think I can remember?

Mark: You know, it could be next week. Maybe someone's going to listen to us next that's on the list.

John: So, when we start, what I want to talk about and I want people to think about is, today, we are living in a state of siege in our minds with the fear that goes on. We have a state of siege, and I ask people to think about this. Do you watch more news or less news than you did five years ago? If I ask an audience and ask them to raise their hand, what do you think? How many hands are up, what are the most hands.

Mark: More news.

John: No, less. People are dropping out. They get more news, but they're not watching more news, so the media's getting more uptight and more uptight and more uptight to try to keep us, ...

Mark: And it's not working.

John: ... and they getting more panicked. It's like any business on the downward slide.

Mark: John, thank you so much. I continue to be amazed at how much we learn. Even though I think I understand it, you open up more doors so, until we meet again, thank you so much.

John: Awesome. Thanks.

Mark: Thank you for listening. We look forward to you subscribing. Join us as we uncover and explain the nuances of John’s distinctive approach. For more episodes, visit thedaviesmethod.com. I’m Mark Sylvester, recording at the Pullstring Press studios in Santa Barbara, California.

Start here with Crisis

get the Crisis communications checklist

Check out our blog for more insights and fresh content about how to Effectively communicate when you encounter a crisis.

READ THE LATEST BLOG POST